- Learning time

- 20 minutes

- First play time

- 60 minutes

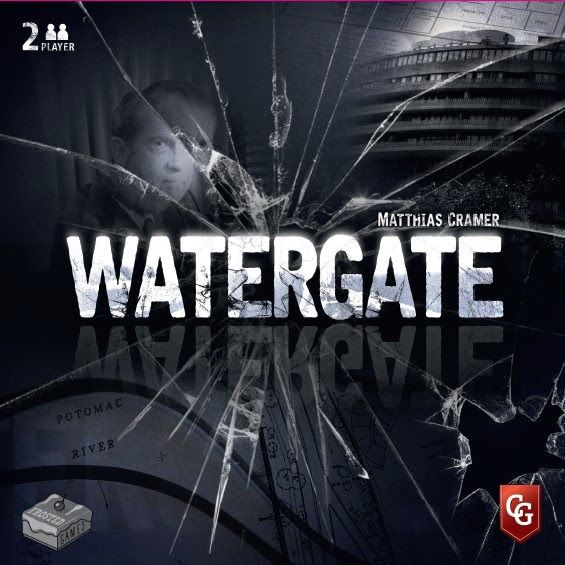

Watergate

Designed by: Matthias Cramer

Between 1972 and 1974, Washington Post journalists (and others) led an investigation into the dirty tricks of President Richard Nixon’s administration which eventually led to his removal from office. In Watergate, two players represent either side of this fight, with Nixon fighting to reach the next election (measured by ‘momentum’) and the Washington Post player – the ‘Editor’ – striving to make connections from informants and literally join the dots on the board to connect them back to the president himself.

Both players shuffle their respective deck of cards and deal themselves a starting hand (Editor: 5 cards, Nixon only 4). The board faces the Editor, with the majority of it showing a corkboard in the Washington Post office. To one side is the Research track – in the centre of the track are placed the Initiative token (white) a Momentum token (red) and three Evidence tokens, drawn from a bag.

A round is played with the starting player – the Editor – choosing one card to play, and thereafter both playing a card at a time until all cards are played. Each card has two different ways to be played – for the number value, or the event. Playing a card for its number value is simple: you reveal the card and use the number in the top left to move either the Momentum token, Initiative token or an Evidence token along the Research track towards you – and away from your opponent. At the end of the round anything on your side of the Research Track is awarded to you: Initiative gives you 5 cards (instead of 4) in the next round, Momentum is what Nixon needs to win (five momentum to be precise – but as well as preventing Nixon from progressing, the Editor claiming Momentum can trigger some one-off rewards as well). And finally Evidence tokens will be placed on the board, either linking informants to president for the Editor, or if you’re Nixon, blocking them off!

You can also play the Event though, which – usually – represent more powerful actions that might affect a number of things on the board; adding informants (or eliminating them) flipping evidence tokens or moving numerous things along the research track. Some (Reaction events) can even cancel out your opponent’s last-played card. The catch with the events is that they remove your card from the game permanently – whereas using the number value instead means the card will come into your hand again.

Finally each side has some special cards (Journalists for the Editor; Conspirators for Nixon) who have powers specific to your side. These are (usually) not one-use only, so you can plan for them landing in your hand again at some point. Once all cards are played, Initiative and Momentum tokens are rewarded and Evidence tokens placed on the board. Then a new round begins, with a new Momentum token and three new pieces of Evidence.

What transpires from the simple options – play a card for the event or number – is a battle for control across three fronts. Momentum is key, because Nixon needs five momentum to win and the Editor, obviously, needs to prevent that. The Editor in turn needs Evidence tokens to connect informants to the president, and Nixon is trying to prevent that. And both players are trying to wrestle the initiative token towards them, because playing that one extra card in each round can be a huge advantage.

As soon as either player reaches their objective, they instantly win.

Joe says

This is a terrific little two player tussle with a brilliantly integrated historical/political theme. My interest is usually piqued by games which explore the dynamics of actual political events, but as a general rule, the shorter and more compact the game, the less integral the game mechanics feel to the theme. You get a short history lesson in the rulebook and then a game that pays little more than lip service to its source. There are exceptions though, and Watergate is one of those, thanks to the brilliant evidence board. Here, as the Washington Post player, you attempt to make physical links between the informants and Nixon. As Nixon you do your best to close those links down. It's simple, but it's such a direct analogy for the actual process of getting at the truth it works brilliantly. The momentum track, by contrast, is a completely abstract concept; but it provides an essential alternate route to victory, meaning both players have to balance their investment on several fronts. The resulting combination produces a thoughtful, insightful experience, but one that doesn't sacrifice the tense tug-of-war of a proper head to head game.

The guru's verdict

-

Take That!

Take That!

It's a game of dastardly deeds. Nixon - the original dastard - might be the villain of the piece, but the Editor has a few tricks up their sleeve too.

-

Fidget Factor!

Fidget Factor!

Turns are swift, alternating between the players, and they speed up as your hand of cards depletes each round. And in any case, you're fully invested in what your opponent is up to on their turn.

-

Brain Burn!

Brain Burn!

Low. Even on a first play, there's nothing too overwhelming here. Having that visual aid for the Editor was a great call by the designer and publisher.

-

Again Again!

Again Again!

Watergate offers some inbuilt variety in the fact you can play one of two asymmetric sides. There's not a wealth of variety beyond that, but the way the cards fall - particularly if you play frequently and come to know your deck - always offers you tactical decisions in what is already a very reactive game.

Sam says

I was wary playing Watergate for the first time, because in the past many of these push/pull two-player games of political control disappear into abstraction from the moment you start playing and I find that without the narrative the game becomes - for me - a little bit dull. But there are some excellent exceptions - the beast that is Twilight Struggle; the very clever Air Land and Sea - and Watergate is another. Although at first glance it might look complicated, it's actually very accessible and I've enjoyed plays with both gaming zealots and less-zealous family. It's not for the faint of heart though - usually there are cries of outrage, or at the very least some mutterings under someone's breath.