- Learning time

- 40 minutes

- First play time

- 150 minutes

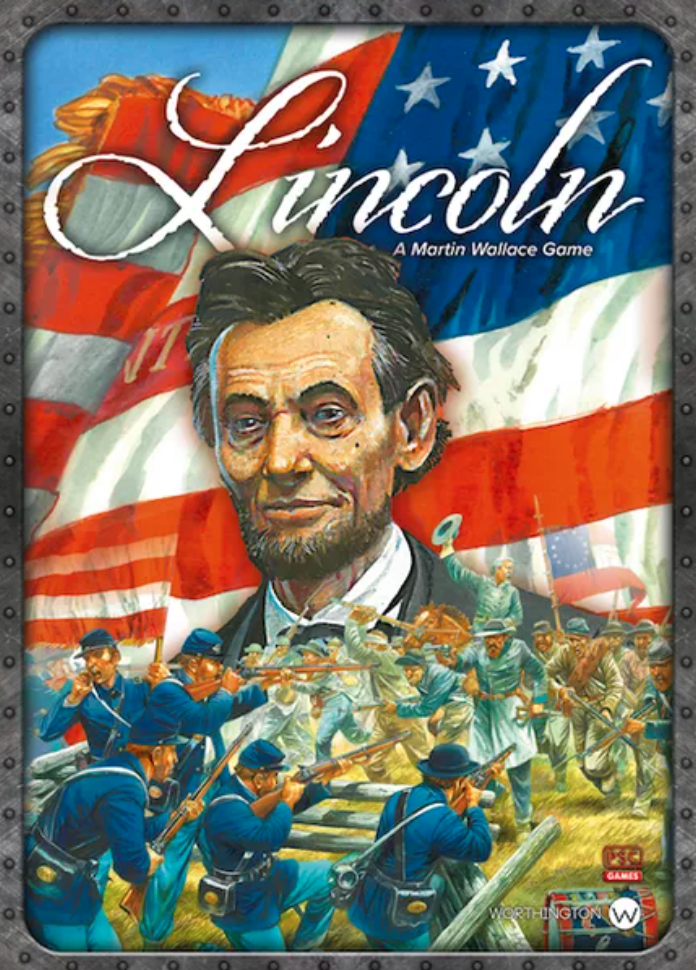

Lincoln

Designed by: Martin Wallace

The Lincoln of the title is Abraham, whose elevation to presidential office kicked off the Confederate’s attempt to secede from the union. In the game, you play either the Union, where you try to ensure history plays out as it did, or the Confederate States, where you’ll attempt to swing the civil war another way.

So it’s a war game, essentially, but with relatively simple rules offering a good degree of tactical flexibility. The board shows a map the players jostle over, each army unit represented by cardboard chits (strength 1-4) in the city spaces, and each city space connected by one or more railroads to the rest. You begin with some army units present on the board but can add more during the game, utilising the precious commodity of cards.

Both the Union and the Confederate player have their own (asymmetric) decks, with asymmetric hand sizes (six for the union; just five for the Confederacy) and, later in the game, more cards will be added to both sides. But each are utilised in a similar fashion. On your turn you take two actions, and the majority of them involve the deploying and/or discarding of cards: most cards offer a number of different ways to use them, and the choices you make here define your success – or lack of – in the game.

The goal is to gain momentum in the civil war, so some cards are used to move armies around between locations, triggering combat whenever you encounter an enemy. Cards played for movement or as a Leader in combat (adding to your strength in battle) get discarded, and will be shuffled back into your deck when you run out of cards. Likewise, playing a card for card action – a bespoke option, written on the card itself – sees your card go into your discards, to return to you later.

But a critical action, considering is deployment: deploying comes in four forms. Most common is adding an army of the relevant strength to the board (following some simple placement rules) but theConfederacy can also deploy Forts to defend from, adding to any existing army strength in a particular city. Both players can play ships to move a marker along the blockade track: for the Union, a stronger blockade decreases the Confederacy’s hand size – unsurprisingly, the Confederacy don’t want that. And finally both sides can push a marker back and forth on the Europe track: Europe are politically sympathetic to the Confederacy, and should the marker ever reach the end of the track, they can claim an instant victory…

Each deploy action costs cards: you not only discard hand cards to pay for the deployment, you also remove the deployment card itself from the game entirely – it doesn’t go into your discards, and can’t be used again. So both sides are slowly depleting their cards, and with them their available options. Simply clinging onto cards to avoid this fate won’t work – you’ll be outmuscled on the board very quickly – so you have to accept that as time passes, your decisions get tougher. The asymmetry extends to the game ending too – for the Union, failing to score at least two points at the point of your first reshuffle or five at the second will gift victory to the Confederacy. But if you manage to score 12 or more at the point your deck is exhausted a third time, you win. You can also claim a (less likely!) instant victory by claiming control of Richmond and Vicksburg on the map. And likewise the Confederacy can grab an instant win in one of two ways – by claiming control of Washington on the map, or getting the marker on the Europe track all the way to the end. Note also that in combat retreats are possible, both sides take damage, and the outcome of battle affects the marker on the Europe track, adding a level of risk and intrigue!

The guru's verdict

-

Take That!

Take That!

It's war! And not a very nice war, either.

-

Fidget Factor!

Fidget Factor!

Low to moderate. Nowhere near as involved as many war games, Lincoln still throws up tough decisions, not to be taken lightly.

-

Brain Burn!

Brain Burn!

It's a balancing act of maintaining and increasing strength on the board with the currencies of cards, blockades and political will in Europe.

-

Again Again!

Again Again!

Lincoln is a reasonably straight-forward game to learn and play, and always plays out as a battle. But within that framework there's a surprising amount of tactical depth to explore. The way cards are added ensures the Union will get stronger as the game progresses, whereas the Confederates get weaker.

Sam says

It's always interesting to me to explore these historical themes, as I tend to only have a passing knowledge of the basics. Lincoln however isn't interested in the past to the point it becomes bogged down with the need to be an accurate retelling - if anything, it's abstracted further from the norm, and even for a 'light' wargame wears the theme relatively thin; to the point where anyone with more than a passing knowledge might actually find it all slightly incongruous. I have to say, I didn't really learn anything playing it. But the key battle - militarily speaking, if not ideologically - is the thing and quite cleverly presented in how the cards define your actions. I like the lightness, but for me personally the game feels quite long, and though I'm generally a big admirer of designer Martin Wallace's games, this didn't scratch the itch in the way some of his designs do. The Confederate start strong and get weaker; for the Union the reverse is true. That's an interesting take, but it does mean the game can feel a little scripted. But for all it's length, it's pretty fast-moving, and the 'deck destruction' mechanic, as Wallace calls it, does lend the whole thing a suitably tense feel.