- Learning time

- 30 minutes

- First play time

- 120 minutes

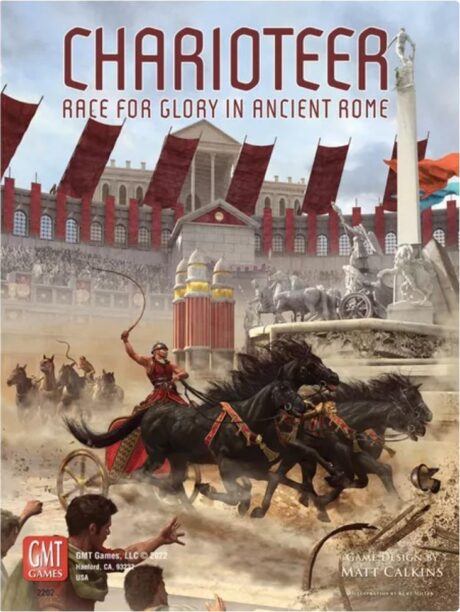

Charioteer

Designed by: Matt Calkins

Charioteer is a racing game from publisher GMT, known predominantly for long, complex wargames. Here however, the rules are relatively straightforward and the game, once you’ve gotten your head around the card system that pushes your chariots along – relatively speedy.

The board shows the racetrack around which players will steer their chariots three times. Players are dealt eight cards and then, over a number of rounds, will play 2-3 cards from their hands to push their chariots along. After the initial round (when chariots move clockwise and ignore overtaking rules) all movement takes place from the leading chariot, then proceeding backwards through the chasing pack, with the trailing chariot moving last of all.

Critical to understanding Charioteer is understanding movement. Cards contain numbers (0-6) that appear inside suit symbols. When you play cards, you’re matching numbers and symbols together, and ignoring anything else on the card. For instance, if I play green 4s, I ignore everything else: including any non-green 4s and any non-4 greens. The total of your movement is the number of matching symbols + the number inside them. So four 4s (4+4) would give me a movement of 8 spaces along the track, whereas four 2s would allow me to move only six (4+2). Note that there are zeroes in the black and yellow suits: in that case, you simply move the number of symbols played (symbols + zero). This is, initially, a bit of a stumbling block, but once everyone has played a few rounds it becomes second nature.

The suits also have their own use. All of them move your chariot, but greens (the sprint suit) tend to move it further. The black cornering suit allows you to double your speed around corners, the red attack suit deals out damage to all players (which slows them down in the next round) and the yellow healing suit gets rid of accrued damage. What this means is that although it feels like your best option is to always move as far as you can, often that’s actually not the case: partly because you might want give out or heal damage, or play a cornering suit around a corner. Partly also because of the crowd and the emperor.

Every round a single card face-up in the middle of the board shows what movements the crowd want to see. If you can match your played cards to any symbol on the crowd card, it bolsters your movement: basically, include the crowd card in calculating your movement as if you’d played it yourself. If you manage six symbols that include the crowd card, you get a bonus tile, drawn randomly from a bag: these can be used on future turns to boost your speed, shield you from damage or allow you to shed cards you don’t want, and so on. The emperor is represented by a die-roll, and – if he’s not arbitrarily dealing everyone damage, he will boost the skill reward for playing a certain suit this round.

After every turn, your skill in the suit you played advances – tracked on your player board, that also keeps tabs on damage. If you please the emperor by playing the desired suit, this skill increases not once, but twice. Each skill remains, for some time, stuck on +1 to your movement of a given suit. But as the game approaches it’s end you’ll find the skills are suddenly worth lots of extra movement: from +3 up to +9 on specific suits.

The game ends when at least one player has crossed the finish line on the third lap. If more than one player passed the line, then the player who went furthest over it is the winner.

The guru's verdict

-

Take That!

Take That!

Playing red suit cards will deal damage to everyone, so nobody is targeted. We actually found this slightly vague hampering a bit generic, but one can't deny it's a very speedy system, designed to keep the race running smoothly.

-

Fidget Factor!

Fidget Factor!

A game of some lulls, but generally short ones, as players work out their best moves according to what cards they have, the mood of the crowd and the whims of the emperor.

-

Brain Burn!

Brain Burn!

See Fidget Factor. However, as you can always see what crowd cards are coming next, there's an element of forward-planning to Charioteer that can feel very satisfying when your plans come together.

-

Again Again!

Again Again!

Set-up doesn't change, but the fall of the cards - and ramifications thereafter - give Charioteer plenty of scope for replays.

Sam says

A strange brew. Charioteer is in many ways, excellent: when familiar with the movement rules, it's fast-playing, boisterous, with a baked-in dramatic arc as everyone improves their skills during the race and hurtles around that final lap. But that getting to that familiarity can be a barrier to entry: it put off potential players with its slightly quirky, unintuitive nature, where damage is dealt in slightly generic abstract ways and the thrill of the race can feel, to some, like it's missing some element of gamery risk: dice rolls, card flips or targeting individuals rather than the opposition as a collective. There's a few edge rules too (you can play a single card, as long as it matches the current crowd card; you can skip a turn to lose all damage) that offset the otherwise *relatively* simple heart. Admittedly the explainer to the left doesn't sound that immediately accessible, but it is almost everything you need to know. And the other thing is that it feels like the real joy of Charioteer is that last lap: we've had fun with it, but it does take a while to get there. So a potential smash for some groups, but a possibly opaque misfire for others.