- Learning time

- 30 minutes

- First play time

- 120 minutes

Europe Divided

Designed by: Chris Marling,David Thompson

Set over 15 years starting circa 1990, Europe Divided pits Russia against the twin forces of NATO and the European Union. What they are fighting over – although fighting is actually slightly misleading, as the real drive here is politicking – are the contested regions in the middle of the board: Moldova, Hungary, the Balkans and so on. Control of these regions scores points… but there are other ways to score too, as we shall see.

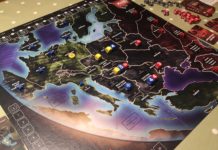

Each side has it’s own bespoke deck of action cards, and you begin with two in your hand plus an Advantage card (more on those in a bit). Players also take control of dice (red for Russia; blue and yellow for the Europe player) three Headline cards, some cash, and a number of armies on the board. If it sounds like it’s already getting complicated, fear not: Europe Divided is deceptively simple once you’ve gained a little familiarity. And it plays pretty fast: over 20 rounds, players each play two action cards from their hands, and – optionally – an advantage card as well. Usually however, players first compare an initiative score on the cards to decide turn order, and then take two actions. The cards dictate what’s possible:

A couple of the possible actions cost cash: building an army, or placing influence on a contested region. To do this, you simply place a die there (the dice are never rolled!) set at value one. This represents your political clout and fledgling power. To increase influence is another action, and – like moving an army – it’s free to do, although if you want to move an army further than a single, neighbouring region, it does cost money. Cards can also be played to raise money, which is critical for Russia in particular at the start of the game, and finally a few cards can be played for a special action: explained on the card itself. Advantage cards are simply a one-off boon that you can expend for the card’s specific advantage on any turn, or keep: unplayed, they are worth a point during scoring.

But why influence? Because increasing influence up to 6 on a die gets control of a region: not only will you score a point for it during the game’s two scoring phases, but you also get to add a new Contested Region card to your deck. And it’s worth pointing out here that the extra card is more helpful for Russia than it is Europe: although the latter is wealthy, as a collective it is also bogged down in bureaucracy, and taking on an extra member state doesn’t help: Europe’s contested cards deck is weak, and actually weakens your options when in your hand and reduces your initiative.

In contrast, cash-poor Russia is at least a single state, and taking control of additional land and resources is more beneficial. In fact, asymmetry is a key feature of the game, from the map to the cards to the Headlines: in the narrative of the game, they are plausible events that occur or not during the narrative. Each headline also potentially scores points if the circumstances on it are realised when the Headline ‘arrives’ – which happens pretty much every other round. If, say, Russia has two armies in Belarus, they get a point. If Europe has more influence than Russia in Poland, Hungary and Czechia/Slovakia, they get four points. And so on. Each Headline can only award points to one side or the other, but as both sides get to choose which Headline gets added from their hand, it gives you time to plan for the future.

And why armies? For two reasons. As well as featuring in some of the Headline objectives, armies can be used to protect your influence in a region or devalue opponent influence and control in a region: If Europe, say, has maximum influence in Poland, Russia can’t gain maximum influence there until European influence drops from a 6 to a 5. Moving an army into Poland costs you the army (it’s removed from the board) but as a result, Europe’s influence drops: now Russia can push it’s own influence up to six! Note too that the actions on contested regions cards (EU/NATO/Russia) may only be played if you have the matching influence there. Armies can run interference too, at a cost: opposing armies in the same region cancel each other out and are removed from the board. Although it sounds pointless – when is war not pointless? – doing so can be worthwhile at times.

At the end of each round, you get two new action cards (reshuffle your discards when you run out to form a new draw deck) and after each Headline is resolved and new ones added, you draw new Headlines also. Halfway through the game the contested regions (and unused Advantage cards) are scored, and then the same again at the end of the final round. Most points wins!

The guru's verdict

-

Take That!

Take That!

A good deal, albeit somewhat abstracted and tactical plan-scuttling rather than overt war.

-

Fidget Factor!

Fidget Factor!

Low to moderate. After that first play things speed up rapidly.

-

Brain Burn!

Brain Burn!

The ideal is to engineer yourself into positions where you pick up Headline points whilst simultaneously denying them to your opponent. But it's tough, with turn order playing a critical role.

-

Again Again!

Again Again!

The action cards don't change, albeit you'll see variations in the Advantage cards. But there's a good deal of variation here - direct from the players. Each and every decision has a ripple effect for the rest of the game, and if the above explanation sounds complex, be aware it pretty much covers all the rules in a few paragraphs!

Sam says

It's pretty difficult to abstract any part of history into the simple mechanics and reductionism of a game, and recent history especially so. The dust hasn't settled, the wounds are sore, the idea of objectivity is almost impossible. For that reason some will have reservations about Europe Divided, but I find it fascinating. The flavour text of the Headlines didn't really sink in when I was learning how to play, but reading them does give the game more of a narrative depth. The rules are relatively straightforward. And - in my experience at least - it's a pretty snappy affair where the two actions on every turn (only 40 in the entire game!) despite being heavy with portency, are limited enough to prevent the game stagnating into a morass of indecision. I like it, and I believe players who are drawn by the theme and enjoy a combative style of game are going to like it too.