- Learning time

- 60 minutes

- First play time

- 180 minutes

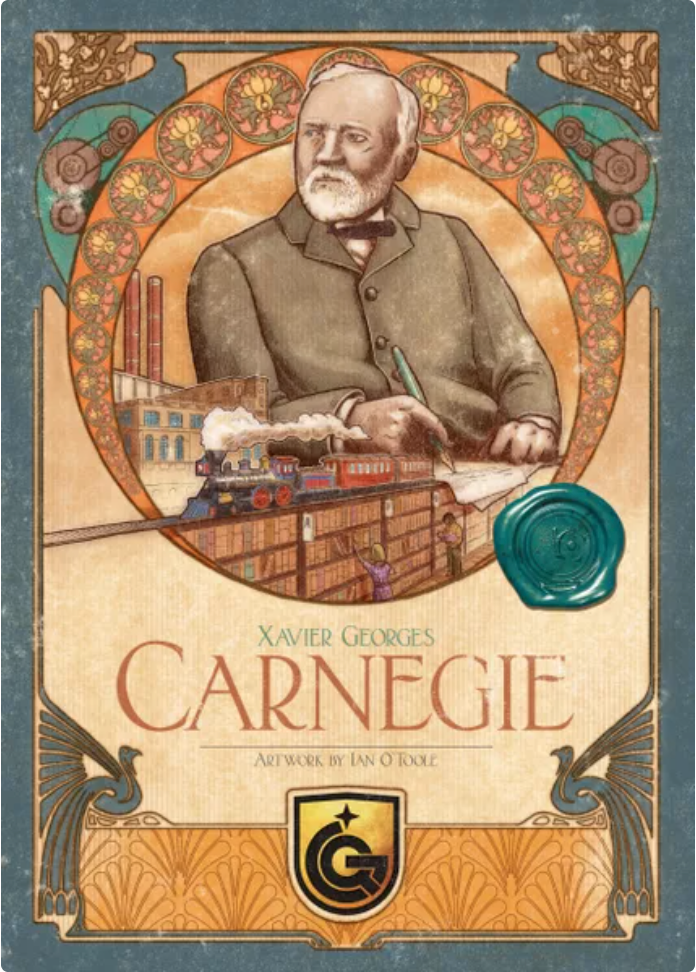

Carnegie

Designed by: Xavier Georges

Taking direct inspiration from the life Andrew Carnegie, Carnegie the game sees you overseeing the advance of industry across the USA whilst also – as the original benefactor did – contributing to charitable causes. It’s a fairly complex game, where even a first play or two – and they’re not short! – may have elements of opacity, but we’ll explain the general thrust of it here.

The main board shows a map of the USA, with four principle cities (New York, Chicago, San Francisco, New Orleans), several major cities and some minor ones, all connected by routes. Your primary objective is to build projects in these cities, and try to create a network of connections between your projects that incorporate the major cities. Do that, and improve how they connect (the default connection is by cart, but you can speed things up with a stagecoach, and then a railroad) and you have a sense of what you’re attempting to do. Another board, made up of randomised timeline tiles, has four markers on it representing different departments: Human Resources, Management, Construction and Research & Development – and each of these relate directly to the offices on your personal company board, which is populated by workers. On your turn, you’ll follow the four phases of each round.

Phase one is moving the timeline, selecting one of the departments and moving the marker to the right.

Phase two is income/donations. The space on the timeline may show one of the four regions on the map: if you have workers out on the board they return to your company and bring you income in the process. If the timeline board lets you make a donation instead, you can pay cash to the bank and put a disc on the donation chart at the top of the board: we won’t go into that in-depth here, but suffice to say each donation offers ways to score points at the end of the game.

The meat of the game is phase three: using departments. Every office in your company that matches the current timeline marker will activate, as long as there is at least one worker. Human Resources offices allow you to move workers around to where you need them in the building. Management gives you avenues of sending off workers to generate cash or goods cubes. Research & Development lets you develop projects: literal tabs that slide out of your factory, generating future opportunities for building and wealth. And Construction lets you realise those projects: placing workers out on the map and constructing the projects on the map. This last option is critical in both getting workers on the map (for income later) and improving your income as you build even more projects.

There’s much more to be said about Carnegie, but without the board and pieces in front of you this description would run out of trail. But what’s crucial to note is that when you choose an action, all the players get to activate it: so Carnegie, as well as being a machine of many moving parts, also offers some rather passive-aggressive interaction. Taking the turn that isn’t best for you might actually be the best move if it’s rubbish for someone else, whose offices are empty for instance. After 20 rounds the game will end and players score points in a few different ways, but most of all their built-network on the map and donations made in the donation chart. The player with the most points wins, and is called Andrew for the remainder of the evening.

The guru's verdict

-

Take That!

Take That!

Indirect, but no less palpable for it. Nobody is going to strongarm their way into your company or whisk away employees. But the action-selection process means that some actions are better than others at different times... for different players. So choosing accordingly, in order to minimise progress for competitors, is a key part of the game. Go capitalism!

-

Fidget Factor!

Fidget Factor!

With two or three players who are familiar with the cogs in Carnegie's machine, it's low to moderate, depending on how coherent strategies are and obvious choices being available (or not). But a first play or two, particularly with three or four players, will require patience to understand how everything fits together.

-

Brain Burn!

Brain Burn!

High. Maybe not as high as it first appears, because after maybe your third play things do speed up, but each decision is meaningful and for Carnegie to be experienced at it's fullest, it's probably best that everyone is happy with the inscrutable nature of it's various interlocking wheels.

-

Again Again!

Again Again!

It's long, it's heavy, it's complex. All things that could be a negative or a positive, depending on where you stand. But Carnegie can't be accused of is being one-note, solvable, or lacking variety.

Sam says

How much I like Carnegie really depends on what mood I'm in. Complex puzzles are not my go-to gaming diet, and generally my tastes skew towards more dynamic, laughter-inducing or story-telling games (by story-telling, I mean games where the theme feels palpable rather than games with a storybook, although I like some of them too). Like many modern games (often called euros, although the definition of a euro game seems opaque at the best of times) Carnegie is more likely to prompt a pregnant pause as a burst of outraged laughter. But unlike some of its ilk, where players have no interaction at all, Carnegie does at least offer a lot of chicanery beneath the surface: because everyone gets to take the action you choose on your turn, two things are critical to how well you do: watching the other players, and timing. After several plays - for me - the game still feels more like a complex abstract rather than Adventures of an Industrialist, but that's not to say it's not a good, and surprisingly spicy, design.