- Learning time

- 30 minutes

- First play time

- 90 minutes

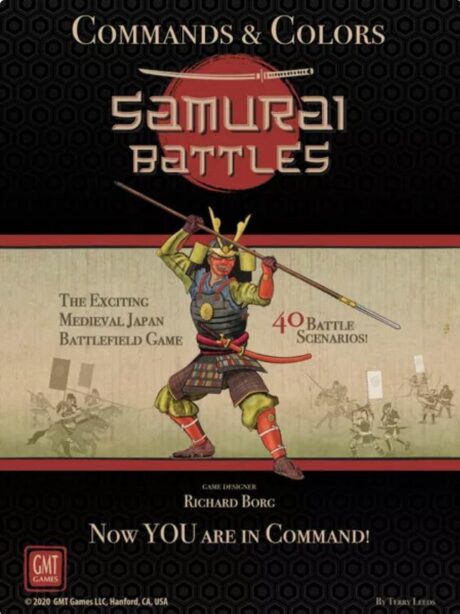

Commands & Colors: Samurai Battles

Designed by: Richard Borg

Commands & Colors: Samurai Battles is an evolution of the original C+C game, following a similar script: two players face off over a battlefield, playing command cards to move their units strategically, attempt to best each other in combat, and the best commander wins.

What ‘the best’ means, exactly, can vary: the game offers a huge amount of variable set-ups. Although the board is always the same landscape tiles and the units themselves, represented by wooden blocks, also change in their make-up and positioning in each scenario. Victory in the introductory game means eliminating five units and/or leaders: we’ll come to leaders in a bit.

Once the game begins, it’s largely a straightforward beast: on your turn you play a command card and follow its directives. The board is divided into three sections, and many command cards allow you move/attack with units in one of these sections. Some might say command a single unit in all three sections; some might give you some other tactical flex like allowing your ranged attackers to all fire on the enemy. Samurai battles has two forms of attack: ranged from distance, and close combat when units are adjacent to each other: both are resolved by rolling dice.

Different types of unit roll different numbers of dice, depending on their strength, but the dice are all the same. If you roll a symbol matching the unit you’re attacking, that’s a hit: one block from the unit is removed from the game. If you roll a sword, that might be a hit, depending on the unit. A flag may mean a retreat for the attacked unit, depending on how many flags you rolled. Each attack comes with risk though; if the attacked unit isn’t forced to retreat, they may now counter-attack. If they are forced to retreat, then some situations allow you – optionally – to pursue them and attack again. This requires the presence of a leader.

Leaders are blocks that can empower units by the mere presence or even galvanise adjacent units of their own. Their strength can be critical; but they’re not impervious to risk, and some attacks will wipe out a leader while the unit itself still survives.

There’s one more symbol on the dice we’ve not mentioned, and that is Honour and Fortune. This symbol allows you to pick up Honour and Fortune tokens. You begin with five, and they are extremely helpful to have in supply: if you’re forced to retreat at all, you have to pay three of these tokens as punishment, essentially representing the cultural shame associated with such an action. They also have a more positive benefit, however, and that is paying to play Dragon cards.

The Dragon cards are a secondary deck that can be played to boost your moving/attacking prowess, or occasionally facilitate some other in-game advantage. The catch is that that they need to be paid for when you play them, and that costs you in the aforementioned tokens: while you will always have a full hand of command cards – you refill your hand at the end of your turn – the tokens and dragon cards are effectively currencies: you can run low, and you can run out. There’s a risk in using tokens to play a Dragon card if you subsequently are forced to retreat. On the other hand, if you don’t play a Dragon card when you can, you might be doing your cause a disservice, and it’s judging these risk/reward moments provide the game with drama and tension, as much as movement and combat on the board.

At the end of your turn you can draw a Dragon card for free, or take two Honour and Fortune tokens. The game continues with this back-and-to of strike and counter-strike, until a player hits the scenario winning requirements.

The guru's verdict

-

Take That!

Take That!

Each game is a battle: no gentle resource-conversion or civil trading here!

-

Fidget Factor!

Fidget Factor!

Low, once you're in the door. Whilst the board state constantly changes, meaning tactical decisions can't be rushed, you're invested in what your opponent does and potentially counter-attacking when it's not your turn as well.

-

Brain Burn!

Brain Burn!

Strategy, tick, tactics, tick. Probably more of the latter as you have to adapt to what the other side is up to. Also timing: tick! Some cards will be more powerful at certain moments over others - can you engineer the battlefield into a situation that suits you better?

-

Again Again!

Again Again!

Quite a bit of variety even if you simply play the introductory scenario a dozen times. When you account for the extra scenarios, different units and variable objectives, the replayability is off the charts - as long as a combative head-to-head is what you're looking for, of course.

Sam says

Generally I'm not a massive fan of games where you take turns to slap each other around the metaphorical face: they can feel repetitive, attritional, and ultimately dull. But there are always exceptions and I love the presentation, speed and tactical nature of the C+C series (I've played Ancients, but there are others too). It's not bereft of strategic play at all, but the vibe of the game is fast, intense, swingy and, dare I say it, silly. In a good way. Risk in games like this feels fun: whilst I have a fondness for Chess based partly on nostalgia, as a game experience it's comparatively dry and mathematical. In comparison Commands and Colors, despite its austere appearance, is a festival of fun: chucking dice, moving units, attack and retreat, and once you've played a game or two, turns are super-fast and each play lasts about an hour - often rather less! And the Samurai theme isn't lazily pasted on as an afterthought: the various scenarios are based on real-world battles, rooted in history and explored in the rulebook. But games are meant to be fun, and the joy of C+C is how it squeezes play from the history in a way that is loyal to its objective, as well as its inspiration.