- Learning time

- 60 minutes

- First play time

- 180 minutes

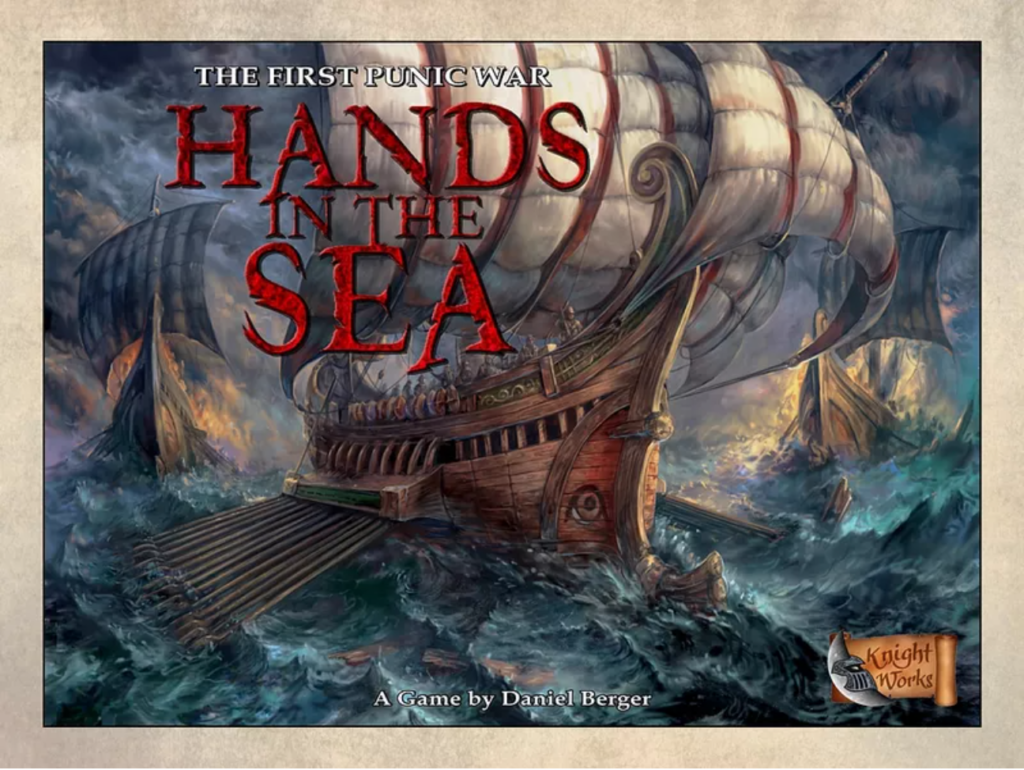

Hands in the Sea

Designed by: Daniel Berger

Hands in the Sea is a two-player game where one side is Rome and the other Carthage. The game traces – or reimagines – the path of the first Punic War, as both sides struggle for control around the Mediterranean in the 3rd century BC. There’s quite a lot going on in the game, but we’ll give a broad overview.

Both sides begin with several towns, cities and a capital on the board, which serves as a map of the region. Worth flagging at the outset is all these locations under your ownership represent a kind of network, in that they are supplied from certain locations. If a town or city is cut off from the rest of your network by being non-adjacent, it’s no longer in supply, and is effectively redundant to you.

So part of the battle is about interfering with each other’s networks, attacking locations and claiming them as your own. How? By playing cards. Hands in the Sea takes the deckbuilding concept and funnels through it numerous opportunities for expansion. Moving, settling, developing, pillaging, getting cash, buying better cards, bribing the enemy, and so on: everything in Hands in the Sea costs you cards. On your turn you have two actions to spend, and your cards facilitate them, providing you with multiple opportunities. Some are simple – discard a card for the cash value on it – some a mite more complicated, for instance to settle a new location you need a location card of a location it can be reached from, a card representing the desired method of transport (wagon/ship) and possibly a colonist card to help settle a city, or an attack card if you’re trying to wrestle the location in question from the other side. Battles themselves are not instantly resolved but take at least a couple of rounds (often more) giving both sides the time to fight back or strengthen their attack/defence. Whenever either side settles (or wrestles) a new territory under their control, they get a new card for their deck specific to that location.

But it’s not just a tit-for-tat battle of area control, because Hands in the Sea has a bit more going on, with several ways the game can end. One is to control all of Sicily, but if you’re so focused on that you don’t see a threat coming to your capital – well, gaining your enemy’s capital is another way to win. If you get all your city and town tokens down, that’s a win. When you win a battle, you capture the opponent’s piece: capture ten pieces for victory! Or you might hit the precious 90 victory point mark, or simply get 25 victory points ahead of your opponent at the end of a given round.

A round ends whenever the Carthage player reaches the bottom of their deck. At this point there is what the game calls a campaign sequence: a random event is drawn that will effect one or other side, possibly punitively, players collect cash and victory points based on the success of the expansionist tendencies across the board: any location you control that you didn’t control at the start of the game (easy to reference by colour) scores you a point. Every city in supply brings you cash.

Outside of all of that there’s further nuance still – both sides have a fleet that roams doing damage, bribes can upset opponent plans, the prestige track plays a part and Strategy cards can be bought to give you an ongoing advantage in the game. If you’re really stumped you can just dump a card for a single coin – your hand size is five so even after you’ve claimed or bought several more cards into your starting deck, it’s still possible to have a hand of brilliance or something slightly more moribund. The game continues until one of the above-mentioned end conditions has been met, or 12 rounds have been played, at which point players tot up points based on how much of the map they control.

The guru's verdict

-

Take That!

Take That!

Plenty. The entire shebang is a battle; or to be more accurate, a series of overlapping battles.

-

Fidget Factor!

Fidget Factor!

Once you're familiar with the game, low to moderate. Some turns are very fast. Others...

-

Brain Burn!

Brain Burn!

...Hands in the Sea has a simple two-stroke engine under the hood, but the directions you can travel with it verge on huge. There are so many options on your turn your first couple of plays - certainly your first few rounds of your opening game - it's probably worth just trying things out. After a while the initial sense of what-iffery begins to fade and the strategies start to come into focus.

-

Again Again!

Again Again!

It's always Rome v Carthage, and it never relocates to Latin America or the cosmos. But there's enormous replayability here from the fact you've so many options to so many cards to build your deck with to so many different ways to win. If you can get up the stairs of learning and have enjoyed it, you're only going to enjoy subsequent plays more.

Sam says

Some games grab you by the lapels and you just love them from your first play (okay, sometimes second, because a first game is always exploratory) . For me, Railways of the World, Quantum, or at the lighter end of the spectrum Just One. Some leave you flat and unengaged. And some you can tell that are excellent in their own way, but it's just not a way that aligns with your tastes. Hands in the Sea was that for me - I found it a little too overloaded with options, a little too much to juggle at any one time, a little bogged down under its own weight. At the same time I found myself admiring it - having seven different ways to end the game at first glance seemed at least three too many. But playing the game these possibilities pulling you hither and thither did start to change from rules into game dynamics, and I began to really appreciate how the politics of power were being played out by this simple two-actions-per-turn system inside this bananas multiple-ways-to-win objective(s). And if I found the multitude of potential actions on my turn (24) and the juggle of combining cards to do some of them somewhat less engaging, I can see that although for me this is a Good game, for the right person - or the right two people - this is a five-star winner. I don't know who they are, but they're definitely out there.