- Learning time

- 40 minutes

- First play time

- 120 minutes

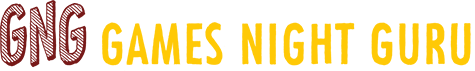

Lords of Xidit

Designed by: Régis Bonnessée

You, the players, are the lords of the titular Xidit, and the land is awash with monsters you are called upon to do away with. The board shows this land, broken by roads into regions, with each road connecting cities.

The game is played over 12 rounds (-there’s a 9-round variant for a shorter visit) which in the game world represent years. In each year, you’ll be recruiting fighters into your party, travelling roads and, one hopes, defeating monsters in order to claim the rewards – the rewards in question being gold, influence and reputation. These three currencies of success will define who wins and loses, with Xidit’s unique scoring system, but we’ll come to that a little later. Firstly, let’s plan our year.

Each player has programming board with which they’ll determine their movements and actions. The board has six ‘slots’ which will be activated, left to right, and what you program into the slots is what you’ll do on the board, as you gallop around on your ‘idrakys’ steed doing derring-dos. The actions are simple: you can move, and the fact each road is one of three distinct colours removes any ambiguity as to where you’re moving to. You can wait – doing nothing momentarily, which can at times be handy – you can take an action at a city.

If the city has a recruitment tile in it, that means there are guys to hire. These take the form of the lowly peasant militia, archers, infantry, clerics and all the way up to the mighty battle mages. When you recruit, you must take the weakest available recruit, and you can only recruit once per year from each city. Take the recruit, and hide it behind your player screen.

If the city has a threat in it – ie, a monster, presumably roaming the city walls and intercepting Amazon deliveries – you can ‘spend’ your recruits to defeat it (doing so means another monster will pop up elsewhere: there are always five at large). Each monster can only be defeated by a distinct set of recruits, and how hard they are to defeat is also recognised in the rewards we spoke of earlier. The monster tile has three rewards, and you may choose two from the gold (put the gold behind your screen) influence (place your sorcerer’s guild piece/s adjacent to the city) and reputation (place your harp pieces in any adjacent regions). Thematically the sorcerer’s guilds build your influence, and the harps your reputation, as bards sing songs of the great day that you sent two archers and a peasant militia to their deaths – but as far as winning and losing are concerned, it’s just about having more of these things in play than your opponents: when the final year is done, everything is counted for Xidit’s slightly bananas final scoring, which demands its own paragraph.

Yes, you score the three currencies of gold, influence and reputation. But! They get scored in a particular order, established randomly at the start of each game. Whomever is in last place on the first scoring criteria is eliminated. Then the trailing player in the second criteria is eliminated, and whoever wins the third criteria also wins the game. So it’s quite possible – perhaps desirable – to just not-come-last in the first two criteria, and thereafter focus your energies on the third!

Note: with only three players, there is a ‘dummy’ player provided by the game for competition

The guru's verdict

-

Take That!

Take That!

For a fantasy-themed adventure of recruitment and fighting, there's not as much as you might imagine. The interaction here is more a confection of races - to grab the best recruits, to defeat certain monsters. Not least to have the most of the critical influence, recognition and gold. You might assume your crew is going to sashay into town and defeat that one-eyed gorgon, but no! Someone got there before you. It's worth keeping an eye on where everyone is on the board - and what their intentions may be - when you program your moves.

-

Fidget Factor!

Fidget Factor!

Low. Although Xidit couldn't be described as a short game, it's reasonably fast-moving. Everyone programs at the same time, then resolves in clockwise order from the starting player over six turns. Moving and recruiting are super-fast. Defeating a monster only marginally slower.

-

Brain Burn!

Brain Burn!

Xidit is a really tactical game, where you're constantly reacting to the game state around you. Grand strategies don't really come into it, but decisions are relatively simple in essence. The brain-burning is more about anticipation and maximisation: what others are doing, and how to keep pace.

-

Again Again!

Again Again!

If you like the 'programming' aspect of Xidit, then the game is inherently varied in that the monsters and recruitment tiles always come out in a random order, and so do the three scoring criteria. The overarching goal never changes, but there's something very satisfying about pulling off a rewarding round.

Sam says

You're hampered by two things - one is that even if you keep track of the guilds and harps out on the board, everyone's gold is hidden - along with their recruits - behind a screen. By the time twelve game years have passed, only the card-counters amongst us will have any clue how rich anyone is. The other is you simply don't know what anyone has planned: they might pull out a spectacular final round and go from tortoise-like lagger to suddenly in-contention. I like that. There's a couple of wrinkles we haven't mentioned. After the fourth, eighth and final year, there's a census where players can show how many of each type of recruit they have: having the most gets you a small, but possibly game-changing reward. But players can choose not to reveal (or to only partially reveal) as doing so gives away information on what you might have planned. The other is the 'Titan' monsters, who appear toward the end of the game, and double both as a finale and a kind of balancer to having an unlucky combo of recruits. As unthematically bonkers as it is, I do enjoy that programming aspect of Xidit. And although it's a lot simpler than it initially looks (and sounds) Xidit demands a bit more focus and interaction than first appears: who is picking up the most cash? Who is being honest or reticent during the census? Can I defeat a particular monster before player X does? And what's great is that all these things are simply emergent in the play itself: the rules are just the mechanics of moving around, getting recruits, then spending them for rewards. Even though I'm not a huge fantasy fan what I like here is how from that not hugely-inspiring premise, a more interesting game emerges through playing. There's two downsides. One is the potential for a miscalculation in your programming to throw everything for a loop and giving you a lot of work to do to become competitive again. The other - the flip side to that coin, really, as 12 rounds gives everyone time to make mistakes! - is that the game can feel quite long and, to an extent, a little repetitive. The short (9-round) version accounts for that, but could feel a little less dramatic as a result.