- Learning time

- 40 minutes

- First play time

- 150 minutes

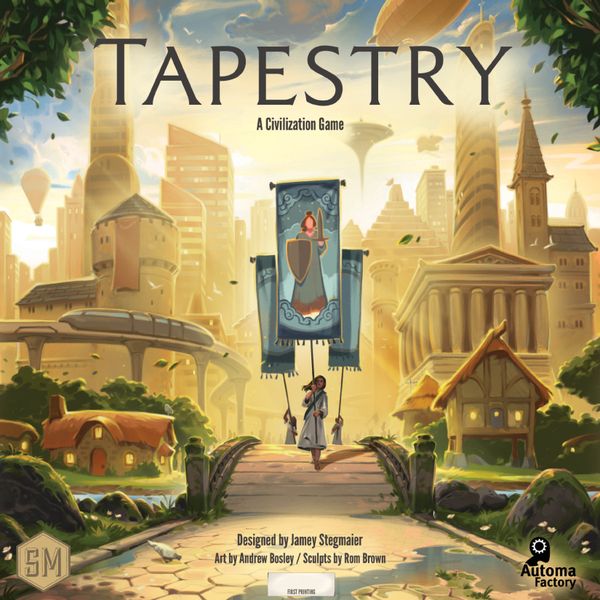

Tapestry

Designed by: Jamey Stegmaier

Tapestry is a game of competing civilisations, although unlike many ‘civ’ games of yore, it’s both lighter on the rules and a little more abstracted.

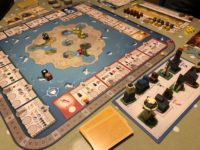

The board shows a map on which the players – at the start – occupy their own small space. Most of it is actually unexplored, and will be ‘discovered’ by adding tiles during play. Players begin with three individual boards: a Civilisation board that gives you an individual power or objective, a Tapestry board populated with income buildings – houses, markets, armouries and farms – as well as places to play Tapestry cards and track your resources, and a City board on which you’ll be constructing these aforementioned buildings.

But the game is really all about the four advancement tracks that surround the map: Military, Science, Exploration and Technology. These tracks are the engine with which you power your progress in the game. On your turn you can do one of two things: Advance or take Income. Advancing is the meat of the game: spend resources (you begin with a sprinkling at your disposal) to move up one of these tracks, and take the action on the spot you’ve reached. Exploration is broadly about finding new areas on the map and claiming the resources there, military advancement is mostly about taking control of map areas, technology aids your civilisation with tech cards that bring various rewards (buildings/resources/points) and science is a track that ‘explores’ in a more indirect and slightly haphazard way – the rewards for climbing up the science track are usually how it pushes you up other tracks in return. All tracks have spaces that trigger building opportunities in your city, other spaces that score them, and spaces that give you Tapestry cards.

Why are you doing all this exploring and conquering and building though? Well, at some point you will run out of resources, at which point you’re forced to take an Income turn. There are four stages to an income turn, but they’re very straight-forward: your bespoke civilisation may have some special ability that activates, tech cards can be upgraded to bring their rewards, your city scores points for completed rows or columns, and you gather more resources based on how many income buildings you’ve built. You also now get to play a Tapestry card: placing it face-up onto your mat and taking an instant reward or benefiting in some way for the next ‘era’ – until your next Income turn. If you’re the first to play a Tapestry card for any one era, you also get some freebie resources!

Freshly boosted, you can now return to pushing your way up the tracks. Two things to note here – you cannot get to the top of all four tracks, so when and where you move up creates divergent paths as to how different players score different ways. The other thing is that being the first to reach certain spots on each track brings the reward of Landmark buildings – extra (and extra big!) buildings that you can use to fill large spaces on your city board. This gives each track – particularly in a multi-player game – a sense of racing to it, as you agonise between exploring for extra resources, or claiming that bonus Landmark building before someone else does!

After the fourth era ends – possibly at different times for different players, such is the nature of Tapestry’s advance/income turn structure – players will do a final scoring of their city and tech cards, and the player with the most points is considered the dominant civilisation for the next thousand years – or until you play Tapestry again.

Joe says

I've not played this. I liked Scythe, by the same designer, but not Viticulture - I don't feel a pressing desire to experience Tapestry.

The guru's verdict

-

Take That!

Take That!

Players can 'conquer' each other on the map, but it's less punitive than in many games and doesn't affect how you advance on the tracks.

-

Fidget Factor!

Fidget Factor!

Fairly low. Any 'advance' turn gives you four choices, so the decision space isn't vast...

-

Brain Burn!

Brain Burn!

...that said, how you combine the tracks to interconnect with your Tech cards, Tapestry cards, and map presence is the nub of the game, so assigning randomly is, at best, an unlikely path to victory.

-

Again Again!

Again Again!

There's huge replayability in that Tapestry provides numerous Civilisations to play, and a slab of randomness in the fall of the cards means you can't slice through the game expecting the same thing inside it each time (see Sam Says). That said, the challenge in and around those shifting parameters is always the same.

Sam says

Publisher Stonemaier Games certainly know how to present something; I'm not a fan of miniatures, but a lot of people will love the tactile and slightly cutesy nature of these pieces, even though they're slightly incongruous: it looks more like you're building a bucolic hamlet than a continent-striding civilisation. But the litmus test of a game is how does it play, and on that score Tapestry feels more compromised. Civilisation-building games (which Tapestry claims to be in its subtitle) are usually heavy on story and thematic accuracy, or at least plausibility. Tapestry doesn't really have that: the Civilisations are pure invention and their special abilities are abstracted notions that tie into the game's rules more than its' narrative. The basic premise is flawed from a logical point of view: you can potentially charge up the Science track and have explored space before even discovering metallurgy on the tech track. For some, this is an abstraction too far, and for others the randomness of the Tech and Tapestry cards might make the game feel too swingy or luck-dependent. Personally, I don't mind some luck - and I rather like that wonkiness and inadvertent humour: what is my space shuttle made of? Did I weave it? I haven't even invented writing yet! But that said, the game just felt mechanical to me, and although Tapestry looks lush on the table, my overriding sensation was that it was ultimately compromised by its ambition. However! - if the idea of building a world in 90 minutes instead of the standard civ game's 2hours-to-4-days playtime appeals, you may be okay with those compromises.